|

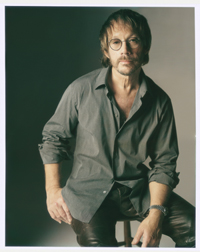

DEATH INSPIRES HIM Warren

Zevon is running out of life, but not inspiration By

Barry Gilbert |

| Warren Zevon, 2002 |

|

DEATH INSPIRES HIM Warren

Zevon is running out of life, but not inspiration By

Barry Gilbert |

| Warren Zevon, 2002 |

August 24, 2003

"How can I complain?" singer-songwriter Warren Zevon said to his son, Jordan, after being diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer about a year ago. "I got to be Jim Morrison for the first half of my life and Ward Cleaver for the second."

"And that's absolutely true," Jordan Zevon says of his father's two lives, one marked by alcohol and drug addiction, and a sober one in which he got to know his son and his daughter, Ariel. "He's been such a stand-up guy. That's what I'm going to remember."

Music fans will remember a songwriter of vision, a performer of passion and a man who, in both song and behavior, seems to have been rehearsing for death his whole life. From "Werewolves of London" and "Excitable Boy" to "Poor Poor Pitiful Me" and "I'll Sleep When I'm Dead," from "Life'll Kill Ya" to "My Ride's Here," Zevon has been looking at death with a cocked eyebrow and sardonic smile for more than 25 years.

When he was diagnosed last August and initially given just three months to live, Zevon already had begun the album that would become "The Wind" (Artemis Records, scheduled for release Tuesday).

Two songs had been written: "Dirty Life & Times" ("Some days I feel like my shadow's casting me/Some days the sun don't shine") and "She's Too Good for Me," written for his girlfriend, Kristen.

The CD is one of the strongest of Zevon's career, a collection of beautiful ballads and raucous rockers that are energized, but not overshadowed, by a little help from a lot of Zevon's friends: Jackson Browne; Bruce Springsteen; Don Henley, Timothy B. Schmit and Joe Walsh of the Eagles; Emmylou Harris; David Lindley; Tom Petty and Heartbreakers guitarist Mike Campbell; and Ry Cooder, among many who offered their services after Zevon went public with his illness.

But "The Wind" stands on its own. Knowing that the artist is dying makes the songs that much more poignant, that much richer, but that knowledge isn't necessary.

Born in Chicago on Jan. 24, 1947, Zevon is the son of a gambler, a man he calls "an LA gangster." His family moved a lot while he was growing up, and his musical education consisted of classical piano. In his late teens, he attempted to become a folk singer in New York - some of those early tracks recorded as half of Lyme & Cybelle are just now being released.

It would be a few more years before the release of his critical breakthrough, the Jackson Browne-produced "Warren Zevon" (1976); during this period he sang on jingles, landed songs on the "Midnight Cowboy" soundtrack ("She Quit Me Man") and a Turtles B-side ("Like the Seasons") and drew a paycheck as the director of the Everly Brothers' backup band.

But the first glimpse of the Zevon he was to become came in 1969. That was the year he released - to little notice and less acclaim - his debut album, "Wanted: Dead or Alive."

"Well, one of the reasons I can't complain about my present circumstances is that I've always written about death," Zevon told VH1 during the making of "VH1 Inside/Out: Warren Zevon," a too short, at times painfully honest account of "The Wind" recording sessions and how Zevon's illness affected them. It debuts at 9 p.m. Sunday.

"Hemingway said all good stories ended in death, and I write songs about death and violence for the same reason. ... I like to think I have s ome goodhearted, romantic impulses now and then, but for the most part I write a different kind of song."

Zevon's "present circumstances" also meant that "The Wind" would be a different kind of album. Musician Jorgé Calderon met Zevon in 1972 when Calderon, as a favor to a mutual friend, bailed Zevon out of jail after a DWI arrest. Calderon became Zevon's bass player and frequent co-writer, and he co-produced "The Wind."

In the past, Calderon says, he would press Zevon to write the music first before collaborating on lyrics, to make sure the record would sound like a Zevon record. For "The Wind," "most bets were off."

Writing under a deadline

"We were writing at such a fast pace, because we just didn't know," Calderon says by telephone from California. "The doctors gave him three months. That was a good thing (for the music) because we didn't think too much or analyze too much. We'd write the song, record it the next day, and we were working on the phone at all times of the day."

Ideas came at all hours and from all directions, says Calderon, who has played and sung on projects by artists ranging from Browne, Cooder and Leonard Cohen to Lindley and Steve Vai.

Calderon said "Numb As a Statue," for example, was "jump-started" by a phone call after Zevon had taken some pain medication.

"He called me on his cellular phone. He'd walked from his house to get some medication at the pharmacy because he was starting to get pain, so he calls me and says, 'You know, I'm numb as a statue, I need to beg, borrow or steal some feelings from you.' He gave me that whole chorus."

Calderon says writing with Zevon is "like being a tailor."

"I'm using things he's said," Calderon explains. "Like the part (in 'Rub Me Raw') about his father ('the old man used to tell me, son, never look back'). I knew what he was going through, how he felt, he was at home, so I'm putting myself in his place and using the things we had already talked about."

"Numb as a Statue" is an example of how the songwriting, in many cases, stands apart from Zevon's condition. It could easily be about someone who is emotionally crippled.

Jordan Zevon, who served as executive producer and backup singer on the project, says, "The beauty of his songwriting is that you can apply it to what's relevant for you. I'm really proud of it."

Calderon says: "Take the example of 'Prison Grove.' We know it's about his death sentence, but other people might take it that we're talking about the death penalty.

"Or in 'Keep Me in Your Heart.' We know he's saying goodbye, but another person might think he's going away for a while."

There is no mistaking the intent or meaning of Bob Dylan's "Knockin' on Heaven's Door," however, a song Calderon initially was strenuously opposed to recording because he felt that, in the context of the rest of the CD, it was obvious and redundant. They were at actor-singer Billy Bob Thornton's house, and Zevon insisted. So, after copying down the lyrics from a Dylan CD Calderon retrieved from his car, they cut the track on the spot.

"The hardest thing for me was listening to (a tape of that) take in the car," he says. "Every time, it would bring tears to my eyes. Warren just wanted to give homage to Bob, whom he loves."

Many other artists, friends of Zevon's, wanted to pay homage to him. Jordan Zevon and Calderon said they were amazed that so many people - stars - showed up and said they did not want to be paid, although they had to because of contractual considerations.

Springsteen, for example, left his own tour between gigs, chartered a plane and flew to Los Angeles to play and sing on "Disorder in the House," a track that is a metaphor for Zevon's worsening mental and physical condition. In the VH1 film, Zevon, grinning broadly, watches Springsteen play his blistering solo and says when it's over: "You are him!" as everyone in the studio laughs.

"We were grinning so hard, and I'll tell you why," Calderon says. "Bruce brought nothing but joy when he came in that door. He chartered a jet and came in the middle of his gigs just to be with his friend. It was just a joy - he came in and got down to business.

"That scene was a take - he just played his solos, just these feral rock 'n' roll solos. We were looking at him, like, wow, rock 'n' roll is alive and well."

Jordan Zevon says of Springsteen and his father, who co-wrote "Jeannie Needs a Shooter" for Zevon's "Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School" in 1980: "It's really fun to watch them together. And that's the great thing about Springsteen: It really is him, there's no off-stage persona. The other thing is my dad makes him laugh. They get a kick out of each other."

Bad move: avoiding the doc

The elder Zevon has explained that he was doctor-phobic for many years. Or, as he told his friend David Letterman last fall when he was the only guest on a special edition of "The Late Show": "I may have made a tactical error in not consulting a physician for 20 years."

Last summer, Zevon noticed during a concert tour and while working out at gyms on the road that he was having shortness of breath. He complained to his dentist, who immediately sent him to a cardiologist.

"I was lucky," Zevon told VH1. "I got all the shocking news in the course of one day. Now I feel like I'm irritating people because I've exceeded predictions that I only had a few months (to live)."

But Jordan Zevon doubts that regular checkups would have discovered the mesothelioma, a rare form of lung cancer linked to inhalation of asbestos.

"It's possible that anything short of a full body scan couldn't have prevented it," he says. "But I'd certainly hope that any fan who wants to learn a lesson from this will. I'll be going to a doctor twice a year for rest of my life. Avoiding the doctor does not keep away the diagnosis."

Jordan Zevon said the work of completing the album contributed to his father's hanging in. He says that when everyone took a break from recording over Christmas, "it really slowed him down. Work pushes him."

Calderon says: "After Christmas, he stayed home and never got back to the studio. His condition really hit him, and we had to wait for him to snap out of it."

The remainder of the vocals were done at Warren Zevon's home.

Still, Jordan Zevon says, his father had the goal of finishing the CD.

"First he joked that the goal was to see the next James Bond film," Jordan says. "Then, more seriously, let's see the new grandkids (Ariel gave birth to twins shortly after the album was completed), then let's see the next 'Matrix' movie. He was always dwelling on the next thing."

Jordan Zevon says he doesn't think his father has a favorite song, one that he'd want fans to remember him by.

"I doubt it. There's been such a collection of songs - he put them out there, and anybody can find the song that means the most to them," he says.

"There's a lot of love out there (from fans). That's the main thing that, if there's something, as his son, that I'd like people to realize, it's that even though he wrote about death and there's an edginess to the music - it's not mean, and he's not a mean guy. He's a good guy and a great dad."

Calderon says: "Sammy Davis Jr. was his hero. He told me he saw him and it changed his whole life. It's an odd combination of wanting to be a showbiz guy and be a writer of serious songs and a writer of crazy songs.

"Jackson (Browne) told me: 'He always was the best of all of us, the best of me, the best of (Don) Henley and all those people from that time in California.'

"I said, 'You're right.'"